Liberty Hamilton

How does the brain process natural sounds?

My current research is focused on how the brain processes sounds -- in particular, natural speech. In my postdoc, I use electrocorticography (ECoG) to study how speech is processed in the human brain. In my PhD research, I used optogenetics and computational modeling to investigate how interactions between excitatory and inhibitory cells in the auditory cortex influence perception. Prior to my PhD, I used functional MRI, structural MRI, and DTI to study changes in the brain associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and ADHD. More details follow below. You can also check out my CV.

My postdoctoral research in neuroscience

In Edward Chang's lab at UC San Francisco, I studied speech perception in the human auditory cortex using ECoG. In particular, I investigated how acoustic and phonetic features are represented across the surface of the superior temporal gyrus (STG), a brain area known to be critical for speech perception.

The following video shows the neural response to a natural sentence stimulus - "Yet they thrived on it". Electrodes on the superior temporal gyrus are colored according to the amplitude of the response at each time point. Darker red indicates a greater response compared to mean baseline activity. The signal plotted here is the Z-scored analytic amplitude of the neural response, bandpassed in the high gamma (70-150 Hz) range, which has been shown to correlate with multi-unit firing of neurons (Ray and Maunsell 2011).

Leveraging the high spatiotemporal resolution provided by ECoG, my research is focused on how acoustic features are transformed into invariant phonetic and linguistic representations. I apply computational modeling techniques to simultaneous recordings from low level primary auditory cortex and higher order parabelt areas (including the classic "Wernicke's" area in the superior temporal gyrus) to address this question.

Below, I include a synopsis of some of the papers I've coauthored describing how speech is processed in the human cortex:

(1) Cheung C*, Hamilton LS*, Johnson K, Chang EF (2016). The Auditory Representation of Speech Sounds in Human Motor Cortex. eLife 2016, 5:e12577. http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.12577. *Co-first authors.

- This paper delves into an interesting phenomenon that we have observed in our ECoG recordings, where sites in the sensorimotor cortex appear to be active during passive listening, even when no movements are taking place. This phenomenon has also been observed in neuroimaging studies, and has been controversially interpreted to mean that speech sounds are processed as articulatory gestures. This is called the motor theory of speech perception (Liberman et al 1967, Liberman and Mattingly 1985). This theory predicts that when we hear a sound such as the consonant ‘b’, the sound activates the same areas of motor cortex as those involved in producing that sound. To test this, we had participants listen to consonant-vowel sounds ("ba", "da", etc.) and say those same sounds while we recorded activity from the superior temporal gyrus and sensorimotor cortex using ECoG. We found that patterns of activity in the motor cortex during speaking clustered according to articulatory features. That is, sounds that used the same articulators, like "ba" and "pa", which both involve closure at the lips, showed similar patterns of neural activity. During listening, however, we saw something quite different. Instead, we found that neural responses in motor cortex were more similar for sounds with the same manner of articulation, which is an acoustic rather than a motor/articulatory property. This representation appeared similar to, though weaker than, the acoustic representation in the auditory cortex. These results suggest that motor cortex does not contain articulatory representations of perceived actions in speech, but rather, directly represents auditory vocal information.

(2) Hullett PW, Hamilton LS, Mesgarani N, Schreiner CE, Chang EF (2016). Human Superior Temporal Gyrus Organization of Spectrotemporal Modulation Tuning Derived from Speech Stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(6): 2014-2026. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1779-15.2016

- In this paper, we investigated how spectral and temporal modulations in speech are represented across the surface of the human auditory cortex. Natural sounds, including speech, are composed of both temporal modulations (for example, repetitive clicks or broadband sounds) and spectral modulations (for example, vowel sounds). We know from previous research that the auditory system appears to be optimized for the spectrotemporal features that appear in the natural environment (for a great overview, see Elie and Theunissen, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014). Still, it was not clear how these spectrotemporal modulation features mapped onto the brain's surface, particularly in higher order auditory cortical areas that do not show organized tonotopic representations like those seen in primary auditory cortex. In our study, we played sentences to patients with implanted ECoG grids over the STG, and found that STG exhibits an organized gradient of representation from low spectral/high temporal selectivity in the posterior aspect to high spectral/low temporal selectivity in the anterior part of STG.

My PhD research

During my PhD at UC Berkeley I studied how the brain processes sound from the level of basic properties of neurons to perception. This took the form of a number of different projects that attempted to answer the following questions:

How do neurons respond to natural and artificial sounds?

Sound is processed by multiple brain structures in a complex pathway starting at the cochlea and moving up through the brain stem to the thalamus and auditory cortex. In the Bao lab, I studied perception in the auditory cortex, the last stage in the auditory pathway. While researchers believe that the brain decomposes sounds into their spectral (pitch) and temporal (time/rhythm) components (as well as loudness and spatial location), these are clearly not the only important features in processing sounds. For example, neurons in the mouse auditory system may be activated by species-specific vocalizations, but will not respond to a pure tone at the same pitch as the vocalization. This suggests that pure tones, which are classically used to describe neurons' selectivity to external sounds, may not be an ideal search stimulus, and that neurons are preferentially active when stimuli are behaviorally or ethologically relevant. My PhD research thus addressed how selectivity to natural sounds (vocalizations) differs from selectivity to pure tones.

How do networks of neurons interact in the auditory cortex?

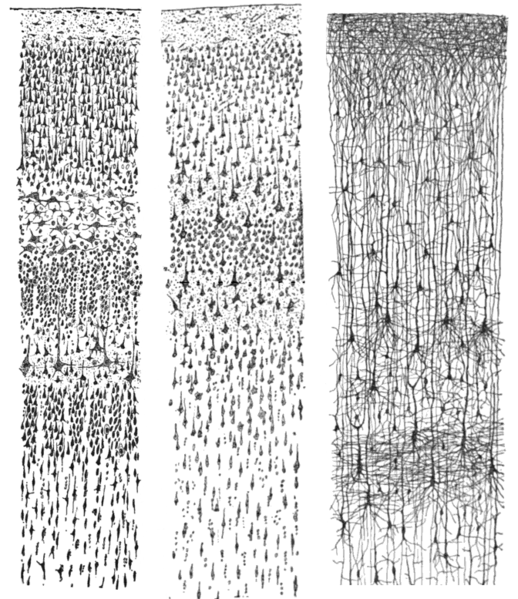

Neurons interact in massively interconnected networks that consist of cells of many different types with many different properties. In the cerebral cortex, the outer sheet of cells wrapping around the hemispheres of your brain, cells exist in six layers.

These drawings by anatomist Santiago Ramon y Cajal, taken from the book "Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex", show this stratification. The relative size and composition of these layers differs somewhat between cortical areas, with sensory cortices (such as auditory and visual areas) exhibiting a larger layer 4, and motor cortex exhibiting a very narrow layer 4 and larger layer 5.

Left: Nissl-stained visual cortex of a human adult. Middle: Nissl-stained motor cortex of a human adult. Right: Golgi-stained cortex of a 1 1/2 month old infant.

In my research I investigate how different cells in the layers of auditory cortex communicate with one another using a combination of computational methods and optogenetics. Optogenetics is a method that allows researchers to identify and control specific types of neurons using laser light. By being able to perturb specific types of cells, we can see what effect this has on the network with great spatial and temporal precision. In 2013, we published a study showing that stimulating inhibitory cells in the auditory cortex enhances feedforward, but not lateral or feedback, functional connectivity across the layers of the auditory cortex. Details are provided here:

Hamilton LS, Sohl-Dickstein J, Huth AG, Carels VM, Deisseroth K, Bao S (2013). Optogenetic Activation of an Inhibitory Network Enhances Feedforward Functional Connectivity in Auditory Cortex. Neuron 2013 Nov. 20; 80:4 1066-1076. Link to PDF.

Which physical properties of sound are related to the perception of musical timbre?

"Timbre" is a property of sound that is often described by a negative definition -- it is all qualities of a sound that are not pitch, loudness, duration, or spatial location. This definition makes it difficult to describe what physical properties of sound are associated with timbre. Thus, we used multidimensional scaling, discriminant function analysis, and linear regression to relate physical properties of Western orchestral instrument sounds to human perception of differences in timbre. Our results are published in the following paper:

Elliott TM, Hamilton LS, Theunissen FE (2013). Acoustic structure of the five perceptual dimensions of timbre in orchestral instrument tones. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 133:1 (389-404).

Previous Research

My previous research with Katherine Narr at UCLA's Laboratory of NeuroImaging focused on structural and functional deficits in the brains of patients with neurological disorders including schizophrenia, ADHD, bipolar, and depression. This work includes research detailed in the following papers:

Hamilton LS, Altshuler LL, Townsend J, Bookheimer SY, Phillips OR, Fischer J, Woods RP, Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Nuechterlein KH, Narr KL. Alterations in functional activation in euthymic bipolar disorder and schizophrenia during a working memory task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009 Dec;30(12):3958-69. [Download PDF]

- In this paper we had patients with bipolar disorder (who were also euthymic, that is, not experiencing either depressive or manic symptoms), patients with schizophrenia, and healthy controls perform a visual working memory task while in an MRI scanner. We measured blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) activity across the whole brain and found that patients with schizophrenia showed significantly lower task-related activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) compared to healthy controls. Bipolar patients showed slightly less activation in DLPFC compared to controls, but this difference was not significant. This suggests that despite similar diagnostic and behavioral features in bipolar and schizophrenia, including deficits in working memory (which in bipolar disorder can persist even during euthymia, when affective symptoms are not present), the way in which these manifest neurally differs between the disorders.

Hamilton LS, Levitt JG, O'Neill J, Alger JR, Lüders E, Phillips OR, Caplan R, Toga AW, McCracken J, Narr KL. Reduced white matter integrity in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroreport. 2008 Nov 19;19(17):1705-8. [Download PDF]

- This paper uses diffusion tensor imaging, which measures water diffusion through the brain, to investigate structural changes in the brains of children and adolescents with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). We found that ADHD patients showed lower fractional anisotropy (a measure of the directionality of water movement) than controls in the corticospinal tract and superior longitudinal fasciculus, which are white matter tracts related to motor actions and attention.

Hamilton LS, Narr KL, Lüders E, Szeszko PR, Thompson PM, Bilder RM, Toga AW (2007). Asymmetries of cortical thickness: effects of handedness, sex, and schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 18(14):1427-1431.[Download PDF]

- This paper describes differences in cortical thickness in patients with schizophrenia, and separates effects due to the disease, handedness, and sex. One hypothesis is that disruptions in hemispheric language specialization may underlie schizophrenia (Crow, Brain Research Reviews 2000). Schizophrenia patients show decreased cortical thickness compared to controls, but it is not clear if normal asymmetries are also affected. By examining cortical thickness asymmetries in male and female left- or right-handed patients with schizophrenia, we found that dextrality (which hand is dominant) appears to have a greater influence on the pattern and direction of cortical thickness asymmetries than sex or disease processes.

For more information, see the Narr lab website.

For a full list of publications, see my academic c.v.

Side Projects |

Code |